Welcome back to Syllabus Scremes, my monthly thematic recommendation series. I can’t help but associate this month — with its dueling themes of (on the one hand) May Baskets and Maypoles, the Floralia of the Pagan rites, and (on the other) of spring weddings and creamy button-ups and the devotion of Mary — with the iconic epic of that most Pagan of Catholics, Sebastian Flyte. Venez! xx

Et in Arcadia Ego

“Even in Arcadia, there I am.” These words serve as the title for the first book of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. The word “Ego” in the Latin phrase presents us with an interpretive challenge. Treated most simply, Ego = I. However, in the syntactic structure of the phrase, the word becomes a wee more complicated.

Now, my Latin is direly in want of improvement (I’m sure at least some of you, dear readers, have a firmer grasp on it than I) but essentially the rub is: (1) who is the “I” of the phrase? and (2) what’s the tense?

Some have interpreted the phrase to read closer to “Even I (who) have been in Arcadia” than my translation. In the context of Brideshead Revisited, this interpretation casts an air of nostalgic recollection for a hyperion, unspoilt time, now lost. At first glance, this may seem like an appropriate interpretation. But I think Waugh had a different read in mind: “Even in Arcadia, there I am.”

Now we come back around to the question of the “Ego” in the phrase. There is a painting by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Rome bearing the same Latin title, and Waugh may have had this painting in mind.

Barbieri painted “Ego” as Death — that unexpected, but ever-present figure. This comes closer to my interpretation of the phrase, and, I believe, to Waugh’s. Though I’ll amend it slightly. For, though the specter of Death features in Brideshead Revisited, it is something more abstract, something more to do with human self-destructiveness, that I read.

So, allow me to come finally to the interpretation I appreciate best: Et in Arcadia Ego: “Even in Arcadia there we are.” By changing the “I” to “We” in the translation, we come to a sort of ‘fall of man’ interpretation. There is no Shangri-La, no Paradise, that humankind could seek, that we would not spoil, for even in a place of highest heaven, we cannot change our human nature.

The books and films in this month’s syllabus are linked together upon a thread by this theme: beautiful people, in beautiful, untouchable places, corrupting things.

Brideshead Revisited (1945) by Evelyn Waugh

The great British novelist and satirist Evelyn Waugh (1903–1966)’s magnum opus was published just as World War II was coming to a close. To the chagrin of Wimsatt & Beardsley,1 I’m afraid I must insist that the reader remember this context, for the historical moment in England at publication only helps to illuminate the book’s themes. This was a turning point in the history of England, as was the period of the novel’s setting, thirty years prior, when the country was emerging from the strictures of the Victorian age.

Brideshead Revisited is subtitled The Sacred and Profane Recollections of Captain Charles Ryder. Narrated by Charles, who comes first to Oxford in the early 1920s from an upper-middle-class London family, Brideshead may at first trick you into thinking that it will be like E.M. Forster’s Maurice, in which homosexual love or longing is subliminated into a special and doomed friendship. And while that is present to an extent, it is the themes of addiction and of a compassionate grappling with spirituality that truly guide this novel.

Charles befriends Sebastian Flyte at Oxford, unexpectedly (I shan’t spoil too much for you) and swiftly becomes enmeshed (though Sebastian should like to prevent it) with Sebastian’s family, passing the next several years in and out of their orbit, while Sebastian himself treads a path none of his friends and family can follow.

I had been there before; first with Sebastian more than twenty years ago on a cloudless day in June, when the ditches were creamy with meadowsweet and the air heavy with all the scents of summer; it was a day of peculiar splendour, and though I had been there so often, in so many moods, it was to that first visit that my heart returned on this, my latest.

Character, Voice, and Theme are strong suits of the book, but perhaps most importantly, is the Setting. After all, it’s in the name: Brideshead is the country seat of the Flyte family and it is always to Brideshead that the various members of the family (Charles included) repair. Though turns in the narrative certainly do happen in London, at Marchmain House, in Tangier and Italy and America, it is at Brideshead where the critical developments in Charles’ relationships with the Flyte family members occur.

I shall leave off here with one final comment — only that Waugh’s prose is scrumptious. In my read of it last year, I underlined so many passages that lifted themselves from the page, preening their wings into shape, and sang to me.

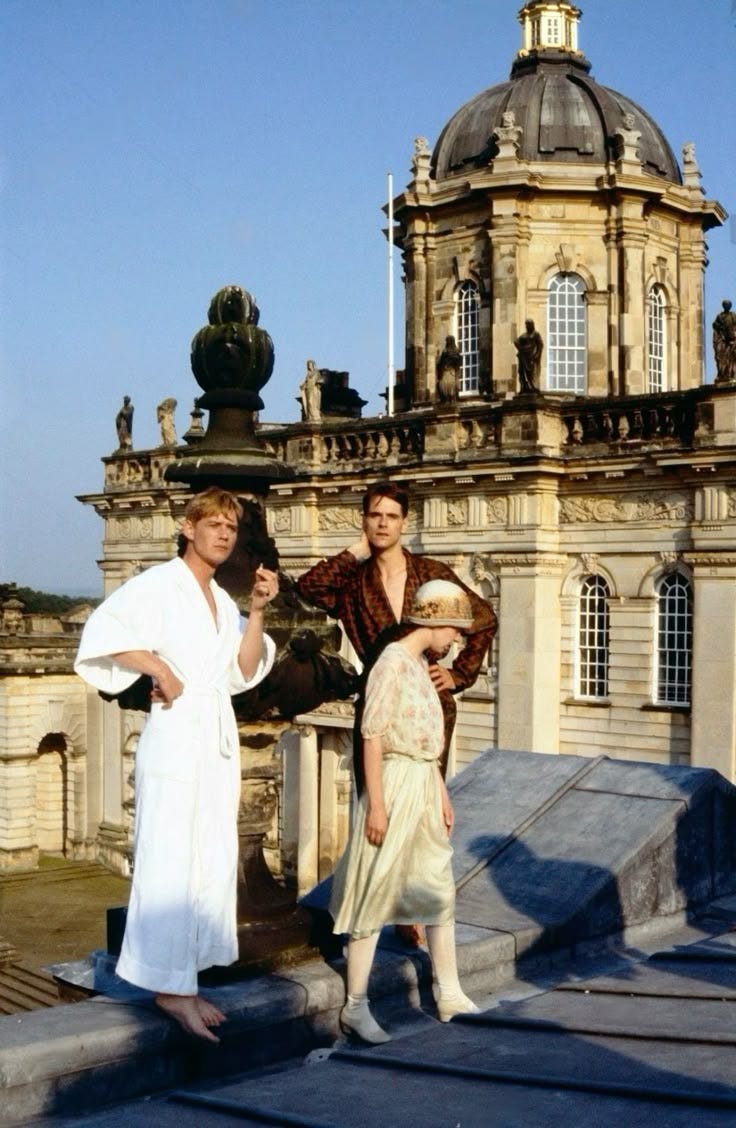

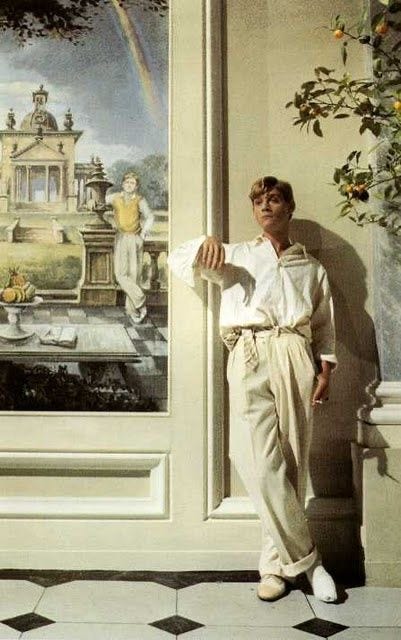

Brideshead Revisited dir. Charles Sturridge & Michael Lindsay-Hogg (1981)

Streaming on BritBox

They really just don’t make them like they used to!

This BBC and Granada production from the ‘80s stands, to me, as an icon of how to make a truly excellent television adaptation of a novel. Starring Jeremy Irons as Charles Ryder, the eleven-episode show pulls an incredible amount of dialogue and narration directly from its source text. (And when Waugh’s writing is so evocative, how could they not!)

Aside from the excellent writing and acting, the show is sumptuously beautiful. I think the conceit of the book — that is, of the story being encased on either end by Charles’ return to the house during his military service in World War II — works wonderfully onscreen. For one, it allows the use of narration — a device I typically abhor in film and television — to flow forth quite naturally. For another, the show’s creators were masterful in manipulating the quality of the light and furnishings and costuming so that those bookends of grim reality can really set off the shimmering visions of what at many points feels a half-remembered dream.

Do yourself a favor! Watch this and don’t ever mention S*ltb*rn in my presence!

The Secret History (1992) by Donna Tartt

As I learned from Once Upon a Time At Bennington College, the 2021 podcast hosted by Lili Anolik, Brideshead (the show) was the thing to watch at Bennington when it came across the pond on PBS in 1982. In an interview with Jenna Pick in 2022, Tartt referenced the writings of Evelyn Waugh as one of her influences, saying “I was reading them obsessively during that time—novels, essays, letters, everything.”

Now, I’ve seen other recommendations pairing Brideshead Revisited with The Secret History, under the auspices of the latter being the American answer to the former, i.e. the ultimate campus novel, New England’s answer to Old England’s dark academia. But I must warn you, Brideshead Revisited is barely a campus novel. Though for the first hundred pages or so, you might be forgiven for imagining all of the whorling tangles will unthread themselves in the quads and streets of Oxford, it actually moves along from that sequestered campus quite swiftly.

The Secret History, however, is most certainly a campus novel, taking place over the course of a single school year (oh, how I love a book with a defined parameter!) at Hampden College (like Bret Easton Ellis and Jill Eisenstadt’s ‘Camden’, Tartt fictionalized Bennington with ‘Hampden’). That limited narrative time and the revelation of the supposed climax at the very outset of the book, not to mention Tartt’s extraordinary character development, make for a delicious book.

For those of you entranced by language, like I am, the book picks up the thread of translation and interpretation I introduced at the top of this letter, as the central cast of characters find each other through an exclusive, invite-only Greek class with an enigmatic professor, and spend great swathes of time translating and debating Latin and Greek.

The Dreamers dir. Bernardo Bertolucci (2003)

Bertolucci has got to have been one of our most sumptuous filmmakers. Not to speak of the other films in his œuvre (The Last Emperor anybody??), The Dreamers is a perfect pairing to Brideshead and Secret History. Like those two books, Bertolucci’s film features a guileless and handsome pseudo-outsider (in this case, an American in Paris during the student protests of the ‘60s) who becomes ensnared by the dangerous eroticism of a brother-sister pair.

Also like the two books, The Dreamers has become an aesthetic touchstone for ‘dark academia,’ which itself is obsessed with a certain sublime beauty and subtle horror. And since there’s no film or TV adaptation of The Secret History, I often see stills from The Dreamers used on Pinterest, etc. in fan casts of Tartt’s novel.

Brat by Gabriel Smith (2024)

The final full-length book for this month’s syllabus is last year’s debut from Gabriel Smith. I’m including Brat on this list almost as an inversion of the theme of Et in Arcadia Ego, and for the parallel primacy of setting to Brideshead. Here too a house is elevated to the role of character. But unlike the Arcadian sublimity of Brideshead, the house in Brat is haunted and staying a night there is torturous to the narrator Gabriel, though he also cannot bring himself to leave.

Other threads from the companion pieces on this syllabus wend their way through Brat — addiction plays a part here too, as does the appearance of a brother and sister who feel subtly demonic.

If you can manage it, I recommend reading Brat in one or two sittings. It will leave you feeling pleasantly, tinglingly deranged.

“Prep Meets Street” in High Noon by moi (2021)

Clothes are key in all of the texts on this syllabus! The sensibilities underlying preppy fashion have their roots in the louche, un-buttoned formality of Oxford and Cambridge in the nineteen-teens and twenties. Have a read through this old essay in which I discuss Take Ivy by Teruyoshi Hayashida, and the evolving style of prep.

Issue 52: Prep Meets Street

This November, I’ll be sharing four High Noon Fashion Trend Reports. For this first one, I’m turning the lens on an emergent menswear culture where formerly distinct styles, ones that might even be at odds with one another, slide together into an entirely new variation of streetwear/sportswear.

Pairing: Sauternes (or Prosa) with Strawberries

In the first chapter of Brideshead Revisited, Sebastian whisks Charles away from an Oxford inundated with ladies there for the spring dances, bringing him in a borrowed motor car to Brideshead for the first time. On the way, they stop for a respite.

“You're to come away at once, out of danger. I've got a motor-car and a basket of strawberries and a bottle of Château Peyraguey — which isn't a wine you've ever tasted, so don't pretend. It's heaven with strawberries.”

–Sebastian Flyte

Château Peyraguey is a Grand Cru Classé of Sauternes. Sauternes, a blend of Sémillon, Sauvignon Blanc, and Muscadelle, is notable for being the smallest of the Bordeaux village appellations geographically, and yet also producing the largest quantity of top quality Noble Rot in the world. Noble Rot (Botrytis cinerea) affects grapes such as Sémillon, causing them to rot on the vine, thus increasing their sugar content and producing the world’s finest sweet wines.

While I have no doubt that in Lord Sebastian’s infinitely charming presence, I would immediately lose all power of resistance to any of his suggestions, I’m a contemporary man in some of my tastes and the idea of splitting an entire bottle of Sauternes, eaten with already sweet strawberries, is a bit cloying to me, as I imagine it may be to some of you, dear readers. If I may be so bold as to amend Sebastian’s pairing, I suggest seeking out a bottle of Meinklang’s gorgeous Prosa biodynamic frizzante rosé of Pinot Noir and having that with a great full basket of the ripest spring strawberries. Prost!

Thank you for reading, and remember, if you’re in New York, to come to the Scremes Report anniversary party on Monday with Cake Zine, Notch, The End, and Let’s Stab Caesar! It’s an open house starting at 5.

The critics William Wimsatt & Monroe Beardsley are most known for their theory of “New Criticism,” which argues for literary interpretation via close reading. That is to say, that nothing but the text itself should matter in a critic’s interpretation. Their overriding demand of literature was that a story “like a pudding” must work. They don’t go in for context.